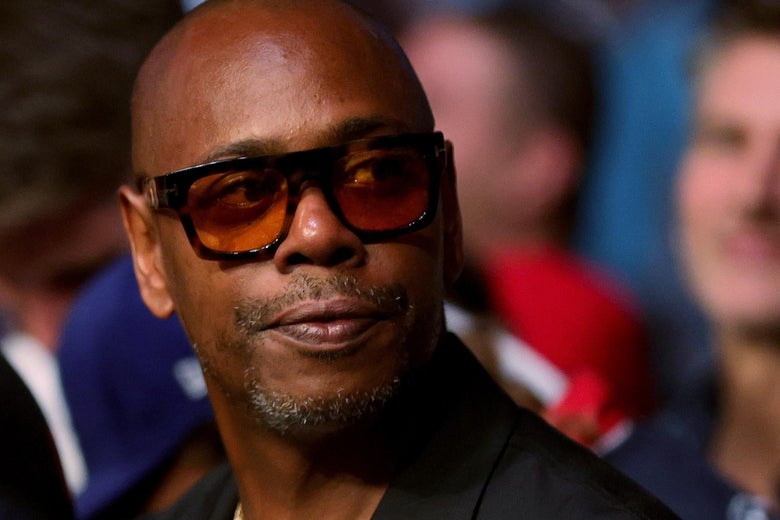

Dave Chappelle I Am Too God Damn Funny

Dave Chappelle Accomplished Exactly What He Wanted To

Dave Chappelle is getting plenty of heat for his latest Netflix special, The Closer. Chappelle's 72-minute bit is squarely aimed at setting the record straight after being widely criticized for his previous specials in which he belittles trans people, gay people, and survivors of sexual violence. He says this is his intention right at the start. We should take him at his word. His routine—controversial as it is—accomplished exactly what he set out to do.

What that accomplishment reveals is not that he isn't funny (he is). It's not just that he is punching down (he is) or that his jokes haven't aged well (they haven't). His latest special confirms once and for all Chappelle was never the progressive darling many thought him to be. In 2019, when Chappelle won the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, Jon Stewart called him the "Black Bourdain," a nod to the widely loved chef and documentarian whose work explored the intricacies of the human condition.

That characterization is somewhat understandable. The beauty, and ultimate demise, of Chappelle's Show was that he deftly and publicly explored the trials and tribulations of Black life. At the time, his comedy was provocative, novel, even revelatory. It makes sense we expected the same nuance with respect to other oppressed groups. But ultimately we were just projecting onto him something that wasn't actually reflected in his work. We expected an intersectional analysis where none existed.

The line that runs through all of Chappelle's comedy is that anti-Blackness is the Final Boss of all oppressions. Everyone else's pain and suffering isn't as bad by comparison, and therefore doesn't deserve the level of outrage and attention it currently gets in progressive circles. Consider one of his opening jokes in The Closer. "I'd like to start by addressing the LGBTQ community directly," he says with a smirk. "I want every member in that community to know that I come in peace, and I hope to negotiate the release of DaBaby." Chappelle acknowledges that DaBaby made "a very egregious mistake" when he made disparaging comments about people living with HIV/AIDS while onstage at a concert in Miami in July. But then the joke takes a turn.

He once shot a n***a and killed him in Walmart. …. Oh, this is true. Google it. DaBaby shot and killed a n***a in Walmart in North Carolina and nothing bad happened to his career. Do you see where I am going with this? In our country, you can shoot and kill a n***a but you better not hurt a gay person's feelings. And this is precisely the disparity that I wish to discuss. …. You think I hate gay people, and what you're really seeing is that I am jealous of gay people. Oh, I'm jealous. And I am not the only Black person who feels this way. We Blacks, we look at the gay community and we say: Goddamn it, look how well that movement is going. Look at how well you are doing, and we have been trapped in this predicament for hundreds of years. How the hell are you making that kind of progress?

This so-called disparity has been at the heart of Chappelle's work for years. But he is finally making it unmistakably plain. On one side we have the Black community dealing with the daily trauma, exploitation, and indignity of living under white supremacy. And on the other, you have the LGBTQ community, which, in Chappelle's eyes, has overcome the worst of its oppression in record time. In this world, these two camps are separate and opposed, with no overlap. (LGBTQ Black people may beg to differ.)

As Chappelle describes it, overcoming oppression is a race, a competition that provokes jealousy, in which progress for one group comes at the expense of progress for another. But gay oppression is hardly a thing of the past. We are still debating whether conservative Christians have to bake cakes for same-sex weddings. Still trying to bar trans people from bathrooms and sports teams. LGBT teens are four times as likely as their hetero peers to consider and attempt suicide. And trans people of color face extraordinarily high rates of violence, unemployment, and housing insecurity. Do I need to go on?

But I also understand where Chappelle is coming from. He's not wrong that anti-Black racism is brutal and ever present. We are just over a year removed from millions of people pouring into the streets to protest state-sanctioned violence against Black people. The same violence we've been protesting against for decades. In myriad ways, Black people fare worse in this country than almost every other racial group. So when I stop and consider the source of Chappelle's supposed jealousy, I hear him saying: If this country truly cared about Black people, we would be outraged and in the streets every single day.

But I'm not writing this to give Dave Chappelle a pass for the comparisons he's making. I'm writing this to acknowledge that Chappelle has always been narrowly focused on Black pain, and that when he speaks of the Black community, he is mostly talking about Black men. He is talking about the experience he knows best, his own. But he fails again and again when his attention turns toward other marginalized groups. "I am not indifferent to the suffering of someone else," he says, acknowledging the meanness of North Carolina's bathroom bill. The moment of insight is short-lived. In the next breath, he's making a set of crude jokes that reduce trans people to body parts.

Over the course of his career, Chappelle has been grappling with a very real victimhood and he has produced lasting art from it (he takes pains in The Closer to describe his work as art). What is unsettling for many of his fans and admirers is that the depth to which he understands his position in the world and the pain that comes with it has not necessarily led to greater empathy and generosity for the plight of others. Put another way, Chappelle was never actually on anyone else's side. His latest special isn't a betrayal, and can't be dismissed as the misguided musings of an out-of-touch and aging comedian. In fact, we're the ones who got him all wrong.

Take one early 2003 sketch from Chappelle's Show, a spoof of an R. Kelly music video in which Chappelle makes fun of Kelly's victims. (The song was called "Piss on You.") Or the "Ask a Gay Dude" segment in which straight men posed obnoxious questions to gay actor Mario Cantone. "Ay yo, I just got one question for you fruitypants out there: What is the rainbow about? I am not feeling the rainbow," asks one man. Have we forgotten the way women figured into many of his sketches? Or as Helen Lewis writes in the Atlantic, "Did none of the recent critics of The Closer notice the way Chappelle has always talked about bitches—sorry, women?"

His early work did not elicit the same ire as his recent specials. This is partially a reflection of the cultural progress Chappelle jealously points out. And his bitterness over this progress for others, and the continued backlash to his jokes, is detectable. He openly rejects the criticisms that he is punching down. And he clearly sees himself as a misunderstood victim. "The transgenders … these n***s want me dead," he says.

So where does this leave us? Is Chappelle a bully? A victim? Can we still laugh at his jokes? Yes, also yes, and yes. He is clumsily and perhaps unknowingly inviting us to consider just how much work there is left to do in the pursuit of equality. And he is also reminding us that intersectionality is hard and complicated. His attempts at describing the power relationships within and between marginalized groups too often falls flat.

At the top of The Closer, Chappelle lays out his mission, nodding to the controversy over his comedy. "I came here tonight because this body of work that I've done on Netflix I am going to complete," he said. "All the questions you might have had about all these jokes I have said in the last few years I hope to answer tonight."

Those questions have been answered. Chappelle hasn't grown or learned from the past criticisms, but with The Closer he has left no confusion about his views. It is time we start believing him.

Source: https://slate.com/culture/2021/10/dave-chappelle-the-closer-netflix-controversy.html

0 Response to "Dave Chappelle I Am Too God Damn Funny"

Post a Comment